This essay, written by the art historian and critic Dr. Jiang Jun, was first published in the catalogue of the Woman - Ma Desheng Solo Exhibition. The exhibition was held at 3812 Gallery London from 15 October to 15 November 2025.

In Ma Desheng's artistic career, stones and the female form have been two significant and enduring themes that continue to this day. This article aims to understand and interpret his artistic practice through the lenses of existentialism and vitalism.

Born in 1952, Ma Desheng, like many of his contemporaries in China, lived under the singular artistic norm of socialist realism. The dogmatism of creation limited their attempts at diversity. The rigid dogma of creation constrained artistic diversity, reducing art to a tool for state propaganda rather than a means of personal expression and life experience.

China’s Reform and Opening-up in 1979 tore open the already loosening ideological and cultural constraints, ushering in an influx of new ideas, artistic movements, and techniques. In Beijing, where Ma was based, this change felt like an emancipation—a lifting of shackles that allowed artists to explore individual expression.

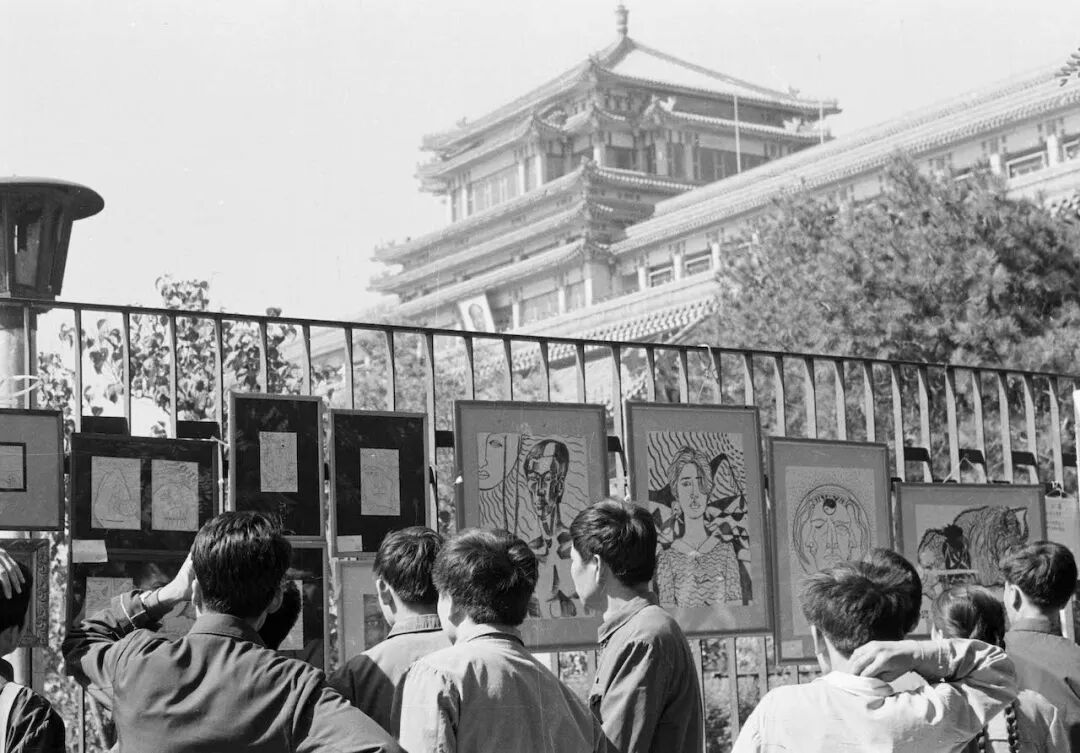

Photograph by Li Xiaobin capturing the scene of the First “Stars Art Exhibition”, taken in September 1979.

In that same year, Ma Desheng and the young members of the Stars Art Group staged China’s first avant-garde art exhibition outside the National Art Museum of China. Unlike official, collectivist narratives, this groundbreaking exhibition championed personal expression, abstraction, and artistic freedom, marking the dawn of contemporary Chinese art. As Ma Desheng recalled in a recent interview:

"The Stars Art Group represented a milestone in the history of contemporary Chinese art. Beyond its art historical significance, it also shed light on the unfettered passion, ambition, and hopes of a generation, which is emphasised in many of my interviews over the decades. At the time, the Chinese art sphere was still heavily swayed by tradition and realism. As young artists, we sought a more expressive and abstract approach, to return to the essence of art and create an entirely new artistic culture and landscape.”

For Chinese intellectuals in the 1980s, existentialism, Nietzsche’s Übermensch philosophy, and Freud’s psychoanalysis were deniable sources of inspiration. In an era when collectivist uniformity was still dominant, existentialism urged artists to introspect and pivot inwardly, seeking the true meaning of individual existence. No longer satisfied with prosaic and formulaic depictions, artists yearned to express their personal perspectives and life experiences through their work.

Nietzsche’s blunt critique about traditional morality and his vision of the Übermensch (Overman) fuelled a deep yearning for human liberation, which had been laying dormant for long, inspiring artists to push the boundaries of personal identity and value. They began putting societal constraints on human nature into scrutiny, exploring themes of self-determination and transcendence. Meanwhile, Freud’s psychoanalysis illuminated the artists with the significance of the subconscious, dreams, and primal instincts—concepts that laid the groundwork for the vitalism in Ma Desheng’s art which I will touch on later. This enlightenment spurred artists to delve into the complexities of human nature and raw emotions that could be tucked away discreetly in deep subconsciousness, rather than shying away from them anymore.

Existentialism, Nietzsche’s Übermensch, and Freudian psychoanalysis together formed the intellectual backdrop of Chinese artistic creation in that era. There is no denying that their influences have been permeating throughout Ma Desheng’s lifelong artistic journey. Reflecting on his work from the 1980s, he once said:

"I had two main creative principles. First, to express genuine emotions—whether social, humanistic, or deeply personal. There were no strict requirements regarding form; it could be abstract or figurative, as long as it was diverse and sincere. The second was the hope and vision young people had for the future of China. Given our historical and cultural context, it was only natural that we were filled with anticipation for what lay ahead. This passion, like a dormant volcano, had been building for years, ready to erupt."

In 1986, Ma Desheng moved to Paris, embarking on a new chapter in his artistic pursuit. Over the years, he traveled extensively across Japan, Europe, and the United States, participating in exhibitions at prestigious galleries and museums, gradually cementing his presence on the international art stage. Yet fate had a cruel twist in store. Though Ma had lived with polio since childhood, he had been able to walk with crutches. However, a car accident in the US in 1992 left him permanently wheelchair-bound. The incident dealt a devastating blow, leaving him physically and emotionally shattered, teetering on the edge of despair.

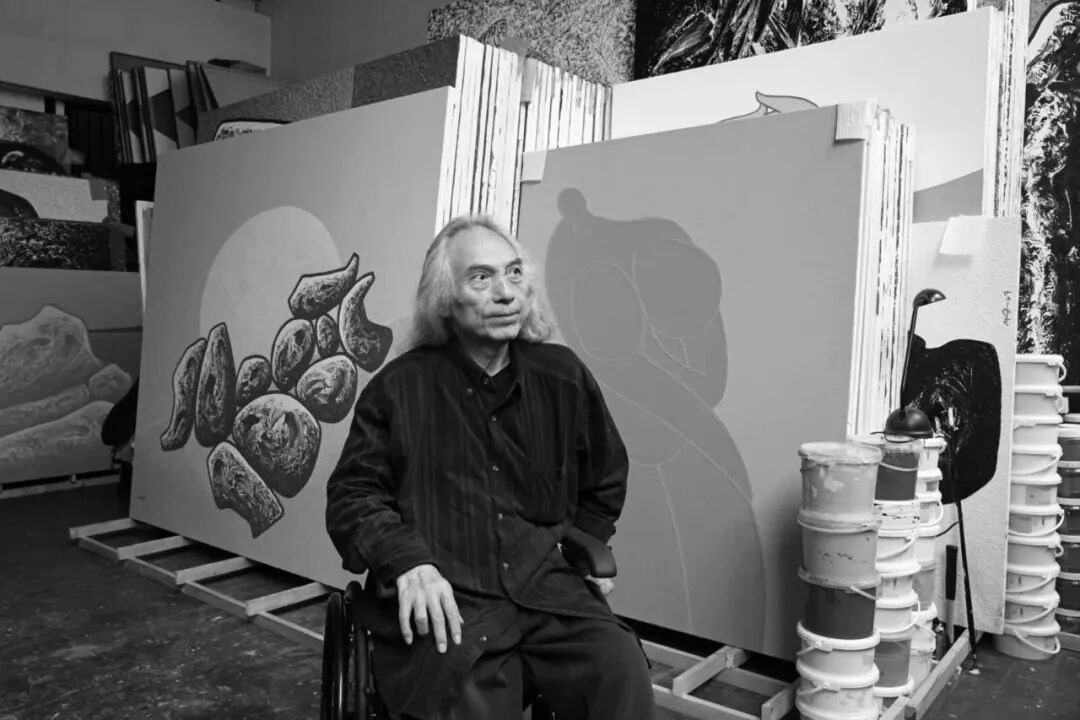

Photographed at Ma Desheng studio in Paris

When many were concerned that he would collapse into obscurity from then on, Ma Desheng, with extraordinary resilience, waged an unwavering battle against all odds. He drew inspiration from Michelangelo, who painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling while lying on his back. Unable to reach high canvases, Ma devised a method where caregivers would rotate the canvas 360 degrees, enabling him to paint freely. Seated in his wheelchair, he adapted his movements, regaining his artistic muscle. Every day, from 10am to 4pm, he immersed himself in painting, spending the remaining hours writing poetry. His unwavering commitment to art was a testament to the Nietzschean Übermensch, embodying the philosopher’s belief that true strength lies in overcoming suffering through sheer willpower.

In 2002, Ma Desheng embraced his an artistic "rebirth." Converting to acrylic painting, he presented the world with a series of works that diverged from his previous styles. “Stone” gradually became his central motif, merging with the female forms in compositions. Through elaborate layering, structuring and reconfiguring, a tower of humble stones biomorph into semi- abstract female forms perching and standing tall, which appear to be both a tribute to Henry Spencer Moore and an evolution of classical Chinese aesthetics. In the meantimes, the subtle impression of Chinese Exotic Rock Aesthetics oozes out of his works. However, unlike Moore’s sculptures or China’s scholar’s rocks (Taihu stones), his depicted stone do not come in continuity or linearity, which sometimes makes it difficult to discern a complete human figure.

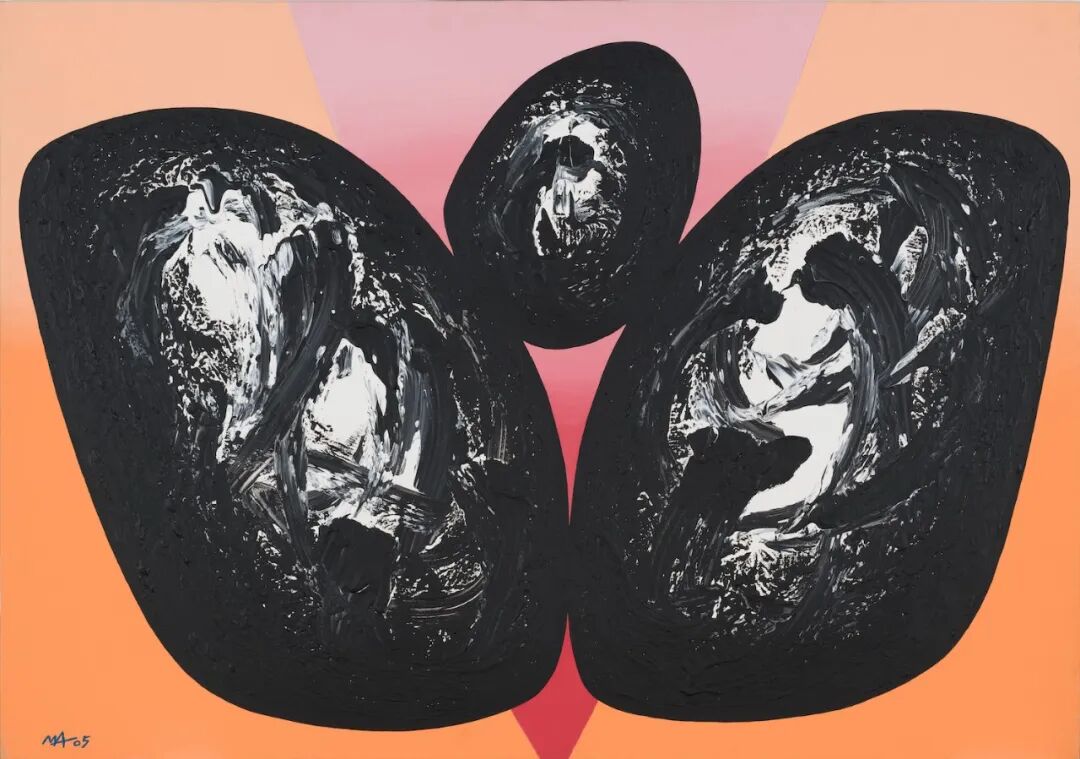

Ma Desheng, Openness-1, 2005, Acrylic on canvas, 114 x 162cm

Staring at Ma Desheng’s stone works from 2002 onward, one cannot help but think of Albert Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus. In this seminal existentialist work, Camus explores the absurdity of human existence through the Greek myth of Sisyphus, who was condemned to roll a boulder up a hill, only for it to tumble down each time he neared the top. This endless, futile struggle mirrors the absurdity of human life.

But Camus’ purpose was not to lament existence’s absurdity—rather, he championed the idea and potency of defiance. Though Sisyphus knows his task may not bring him to anywhere, he persists. His rebellion against absurdity does not change his fate but affirms his existence. Through defiance, man transcends himself.

Ma Desheng, Unwind, 2007, Acrylic on canvas, 140 x 200 cm

Camus' philosophy found resonance in China during the 1980s, as intellectuals sought to make sense of their socio-political realities. In 1981, scholar Guo Hong’an introduced Camus in Sartre Studies, writing:

"Camus was a spiritual guide for an entire generation. He walked toward absurdity with the heavy, measured steps of Sisyphus descending the mountain. He knew that evil could never be eradicated, and it was precisely for this reason that he fought relentlessly to defend human dignity and happiness. He criticized capitalism while also opposing proletarian dictatorship.”

For many, Camus' ideas provided a lens through which they could interpret their own experiences. Existentialism, alongside Camus and Sartre, became a defining intellectual trend in 1980s China. Looking back through Ma Desheng’s life, we would realise the underlying root for his deep attachment to stone reveals itself. The fragmented, non-continuous pebbles in his paintings symbolise his own paralysed body, don’t they? The 1992 accident, much like Sisyphus’ boulder, was a cruel punishment from life, an unforgiving crucible. Now, every movement he makes is like pushing an immense weight uphill, every stroke on the canvas requiring Herculean effort.

But Ma Desheng still creates. Isn’t he the very embodiment of Sisyphus himself? Burdened, struggling, yet forever climbing—unyielding in his defiance against fate.

Ma Desheng, Enchanting, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 150 x 200cm

Through years of relentless creation, he has deeply engraved his defiance against the absurdity of fate into every piece of his work. He battles fate with art as his means of existence, displaying a resilience and determination that is profoundly moving. His journey echoes the famous existentialist assertion: "Existence precedes essence." Humanity must define itself through choices and actions, giving life its meaning. Camus believed that, like Sisyphus, one must face the absurdity of existence with courage, shaping one's own significance through action. Thus, Camus wrote: "We must imagine Sisyphus happy."

Beyond interpreting Ma Desheng’s work through the lens of existentialism, the parallel dimension of "Vitalism" provides another perspective. His stones hold multiple meanings—they are abstracted female sculptures reminiscent of Henry Moore, embodiments of the natural world akin to Chinese scholar’s rocks, and totemic symbols of fertility from ancient art. Within them, one can see the influence of Freudian psychoanalysis, particularly its revelation of human desire—an awakening for Ma Desheng’s generation, who had lived under repression. His work also embodies Moore’s "Vitalism"—a primal life force suppressed by modern civilisation. In early human art, the connection between the female form and fertility worship is unmistakable, a theme Freud explored in Civilisation and Its Discontents (1930). Freud argued that while civilisation advances human progress, it also represses instinctual desires. This perspective sheds light on why artists like Picasso drew from African masks, Moore from Mesoamerican totems, and Zao Wou-Ki from ancient Chinese oracle bone script—all responses to the constraints of modernity. "Vitalism" emerged as a countercurrent within modernist movements, advocating a return to nature and primal instincts, much like the Romantic movement of the late 18th century.

"Vitalism" is a philosophy underlining the intrinsic energy and dynamic essence of life, viewing it as more than just a material composition but an inner vitality that transcends physical form—a remedy to the toxicity of modern civilisation. Henry Moore, a key proponent of this ideology, was deeply inspired by organic natural forms—shells, bones, stones, and tree roots—using them to explore spatial dynamics and sculptural fluidity. When introduced to China in the 1980s, Moore’s "Vitalism" found a dialogue with the traditional Chinese philosophy of Daoist naturalism. The Chinese interpreted "Vitalism" through the aesthetic principle of Qi Yun (气韵)—a concept of vital energy in art—and appreciated the organic flow of life in Moore’s work. This resonance allowed Chinese artists and audiences to decode Moore’s abstract sculptures through the lens of scholar’s rock aesthetics, similar to how contemporary British sculptor Tony Cragg explored digital sculptural forms. By engaging with scholar’s rock aesthetics, Chinese artists absorbed and transformed Moore’s artistic vision, influencing the trajectory of contemporary Chinese art—including Ma Desheng’s own evolution.

Ma Desheng, Gaze into the Horizon, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 200 x 180cm

Ma Desheng, Gaze into the Horizon, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 200 x 180cm

From a comparative iconographic perspective, Moore’s sculptures had a profound impact on Ma Desheng’s “Rock” series paintings. Moore’s semi-abstract female forms, often devoid of detailed facial features, de-individualised the human figure, transforming the female body into a vessel of life force and primal instinct—echoing ancient fertility worship. Ma Desheng undoubtedly adopts this modernist tradition, yet he did not simply replicate Moore’s style. Instead, he fractured Moore’s smooth, flowing forms, infusing his “Rock” series with a more primitivist character. The stacked pebbles in his works evoke prehistoric megalithic structures, such as Stonehenge in Salisbury—silent, mysterious relics of ancient civilisations. His compositions also recall weathered totemic stone carvings from various ancient cultures, carrying traces of time and memory, whispering the long history of human civilisation.

Ma Desheng’s art is a personal epic, written through the language of stone and the female form. On the canvas of existentialism and vitalism, he paints an intimate dialogue between self and fate, civilisation and instinct. His unwavering perseverance is not only an individual triumph but also a testament to the era’s ideological awakening, injecting a unique force into the development of contemporary Chinese art. His works transcend cultural and geographical boundaries, forming a bridge between Eastern and Western artistic philosophies, where the ancient and modern, the traditional and the avant-garde seamlessly converge. In his artistic universe, stones are no longer lifeless objects, but vessels of existence; female figures are no longer mere representations, but emblems of primal instinct and hope. Through art, Ma Desheng proves that no matter how absurd fate may be, no matter how oppressive civilisation becomes, humanity’s pursuit of freedom and meaning never ceases.

Ma Desheng, Gaze into the Horizon, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 200 x 180cm

Ma Desheng, Gaze into the Horizon, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 200 x 180cm