‘The simpler and more natural the mind becomes, the better the world will be.’

Ma Desheng, 2025

‘What is real is not the appearance, but the idea, the essence of things’,Brâncuși

This essay, written by Dr. Katie Hill (the gallery’s Academic and Curatorial Advisor), was first published in the catalogue of the Woman - Ma Desheng Solo Exhibition. The exhibition was held at 3812 Gallery London from 15 October to 15 November 2025.

Outlines

These works by the pioneering artist Ma Desheng, take us on a journey from a female figure cast in sunlight in a simple, black and white woodblock print to vast and vibrant paintings featuring bulbous female nudes, their physical and erotic bodies towering in the space. This journey follows a path from innocence to awareness, an odyssey from an earlier state of optimism to one of awakening. Coming together in a range of series spanning a period of forty-five years, the works emit a powerful visual clarity, echoing the artist’s spiritual and artistic vision of humanism, also expressed through his performances and poetry. They range from the demure to the grotesque, conveying the nude as an archetype or symbolic icon that reaches from the ancient past to modernity, one that takes on a perpetual fascination and mythology.

In the words of the artist: ‘la vie est nue’ (life is bare)[2]. It acts as an artistic trope through which we could interrogate our existence and connection with each other and the world. Through the repetition of this motif, it takes various turns stylistically from small scale to large, from black and white prints to richly colourful paintings in vibrant palettes. These nudes contain, at different moments, lively sweeping brushstrokes and smooth, highly graphic forms, sensuality and formality, veering from the energetic and expressive, to the discreet and clean-cut.

Culturally, these nudes by an artist in the global Chinese diaspora living in Europe, have specific roots in a cross- or inter-cultural experience that cannot be disentangled. Stemming from a longer connection with globalised, metropolitan culture, the interaction was woven into the development of art in the twentieth century, with Paris as the centre of that axis of European cultural exchange between cultural hubs such as Shanghai and Tokyo. Ma has been working for nearly forty years in Paris, the centre of modernism in the 1920s. It is therefore no coincidence that his choice of subject matter, a central theme in European painting historically, is also integral to the development of Chinese artistic modernity in the past century.

Many important figures in the history of modern art in China, including Lin Fengmian, Xu Beihong, Pan Yuliang and Zao Wou-ki (Zhao Wuji), lived in Paris and were strongly influenced by the exploration of colour, line and form that characterised modern movements in art from post-impressionism to surrealism, to pure abstraction. Indeed, as stated in a touring exhibition ten years ago, ‘Their sojourns in France caused a profound rupture with Chinese artistic traditions, and their return to China had a major impact on the formation of an entire generation of artists.’[3] All of these artists themselves painted female nudes. Ma’s nudes could therefore be seen as a dialogue across cultures, at the intersection of Chinese and European modernity, asymmetric modernities that extend into the 21st century.

Picking up on strands of Western modernism in the period following the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) was a concerted quest for artists, who were part of a broader cultural movement seeking a new cultural language of contemporaneity. Ma was at the forefront of this development, actively advocating for freedom of speech and artistic expression, together with other core Stars founders, Huang Rui, Wang Keping and Qu Leilei. Their singular use of line and figuration led artists in China back to an international engagement with art, working with few resources and little or no financial support, unwittingly making connections with a migratory cultural discourse developed previously by artists such as Sanyu (Chang Yu).[4] The extent to which they had access to images of Matisse’s nudes or Picasso’s linear drawings is likely limited to older surveys on Western art, but the reference to these world-renowned masters of Western modernism in 1970s’ China was crucial as a message for cultural liberation for artists and it was a conscious cry for artistic freedom in a grey, colourless world of Mao suits and enforced political conformity. These major figures are still of great interest to Chinese audiences, as witnessed by the 2025 Picasso exhibition in Hong Kong at M+.[5]

Strong graphic qualities and the literal carving out of space in the works also remain in his later paintings, lending them a structural precision. Often, an abstract world in the backdrop is evoked through a simple curved horizon dividing the canvas between a sky and the earth marked out through line and colour. Conceptually, these features act as philosophical markers of the universe, aligning with ancient Chinese notions of the cosmos (天地 heaven and earth) and equally a modernist universalism that bounds the pictorial in aesthetic formality, sealing it off from any recognisable reality. These features run throughout Ma’s paintings, drawing on key strands of his cultural inheritance.

Sketches on cardboard

Ma Desheng, Posture of Curvature, 1995, Sketch on cardboard, 70 x 100cm

Several sketches on cardboard made in the mid-1990s precede the larger paintings, depicting a simple line drawing of a nude, in different poses. Expertly drawn, the outline doubled in yellow, the works show dynamism, volume and depth in their composition, from front and side perspectives. Notable is the curvaceous expression of the legs and feet, the head reduced to a limp phallus, the nipples emphasised as rapid squiggles, and the belly button adding a fleshy detail, all executed in simple lines, echoing figurative painters in the modern period exploring the human form from both Chinese and Western art. The emphasis on line, and the rawness of the image is striking. Why does the figure taper out, and why is the head shrunk to nothing but a floppy-looking pin? The head is rendered useless and flailing in a disturbing erasure of head and facial features as essential markers of identity. The body’s outline dominates the space amplifying its power.

The artist’s response to this question is reductive: ‘we all think too much’ implies a return to being and feeling over thought. It could be read as a contemporary Daoist response of return to nature, but also a reminder of our animal being, the head reduced to just another physiological appendage, alongside our limbs. By privileging the fundamentality of our physical being over the intellectual and refusing to endow the figures with any recognisable identity, Ma foregrounds body over mind, distorting reality in an anti-realist interpretation, as seen in numerous works by Francis Bacon and Henry Moore. Bacon uses his heads to express agony or terror, and Moore’s, though featureless and small, remain upright. Brancusi’s comments on the justification to leave facial features out of his sculptural forms, give an insight into his attention to form and beauty above all: ‘It is such a pity to spoil a beautiful by digging out little holes for hair, eyes, ears. And my material is so beautiful, with its sinuous lines that shine like pure gold and sum up in a single archetype all the female effigies on Earth.’[10] At the forefront of the reduction of form, Brancusi’s work Portrait of Mlle. Pogany (1913) was ridiculed at the Armory Show in 1913 for looking like an egg.[11] When Ma was growing up, his cultural environment would have been saturated with heavily political realism, so his turn away from this in his formative creative emergence as an artist concurs with his interest in Western modernism as an antidote to that restrictive and didactic approach. His awareness of body over mind/mid over body dynamic will be exceptionally acute, since severe physical challenges for him have been a central part of his life. These factors may have a bearing on how we read his work.

Ma Desheng, Revealing Pleasure, 1995, Sketch on cardboard, 70 x 100cm

The markers of the female body seen in Ma’s nudes – the breasts, vulva and belly button – are also present in the earliest female figure in the world, the Venus of Willendorf, a small stone age artefact measuring 11 centimetres in height, dating from 28000-25000 BC, held in the Vienna Natural History Museum. The figurine, like others of that time dotted around Europe, could be a symbol of fertility or an early goddess. Baffling archaeologists, it is impossible to verify its meaning due to the distance of time, leaving it a mystery from the ancient past. The emphasis on the female form, though, clearly has a lineage of tens of thousands of years as evidenced by this figure, endowing it with iconic status, in the literal sense.

Rock nudes

Ma Desheng, Lounge in Joy, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 180 x 200cm

A work from the 2000s, Lounge in Joy (2015), returns to pure formalism, breaking up the form of the body into rounded forms that are another major strand in the artist’s work. In this work, the amorphous shapes form a recognisable, dismembered body, fusing the artists’ interest in primeval forms (the ‘Rock’ series, developed over many years) and life itself, via the body and our existence through it. Its body parts are disconnected, each discreetly balanced to form the whole, in a playful dialogue with the artist’s own sculptures and the interplay between form and non-form, representation and abstraction, two-and three-dimensionality, provoking a question to our visual reception of imagery itself.

Ma Desheng, Pointe, 2015, Acrylic on canvas, 180 x 200cm

Set against a pale abstracted mountain and possibly a lake or body of water, there is a suggested landscape. The curvature of the rocks is modelled to increase the sense of three dimensionality through dynamic thick strokes of paint. A body is a body of rock: how did we emerge? Where did we come from? How are we related to the primal world? Another work in the series, Pointe (2015), similarly evokes rocks, but returns to a coherent (female) body, its dancing posture indicated by her pointing leg, echoing works by Picasso, Matisse and Sanyu. Here, the backdrop is monochrome, in a deep orange, painted with thick, textured strokes that create a contrast to the black and white figure, which is carved out with sculptural solidity. Though highly stylised, her arm points in towards the crutch, indicating her sexuality.

A more recent work from 2024 returns to the aesthetics of these two works. It is a simple formation of five rocks, two large ones placed as giant calves positioned as bent legs, and the three small ones positioned to form a head or body and two arms. The reduced imagery immediately evokes the female nude, without any literal representation, merging the landscape with the body in an effortlessly simple image, against a pale grey arc or horizon, suggesting a world or planet. This work brings together the artist’s engagement with the co-existence of the earth and the body, in a timeless and masterful composition.

Colour nudes

Ma Desheng, Canyon, 2020, Acrylic on canvas, 162 x 130cm

In contrast to the rock paintings, several works from 2019/2020 are cleaner cut, smooth and colourful. One, entitled Canyon (2020), is a succinct formal nude in bright orange, cleanly outlined, against delineated sections in two shades of bright green. Graphically, this work instantly creates aesthetic impact with its emphasis on surface and sense of design, with clearly outlined sections dividing the space in a carefully arranged composition.

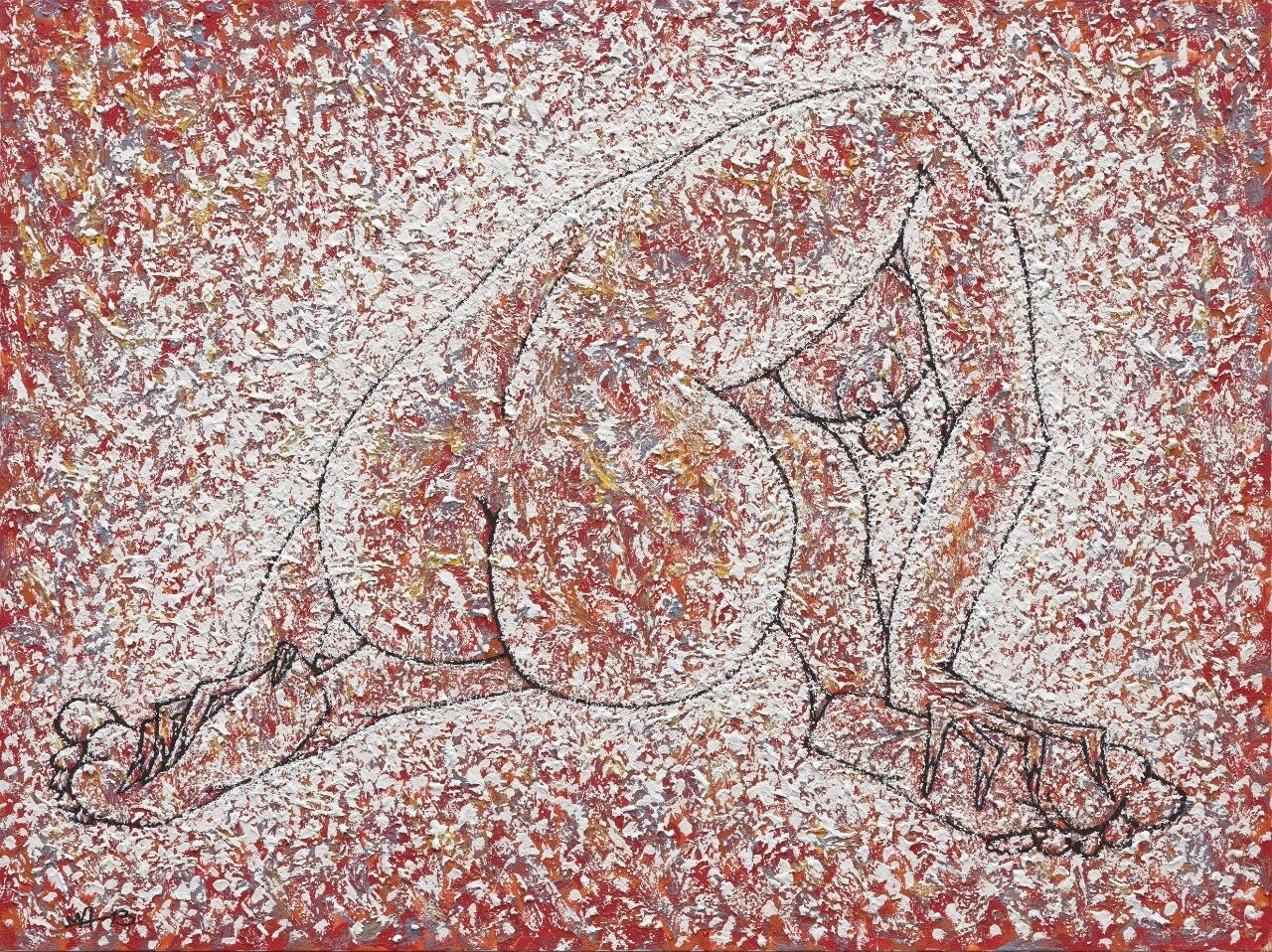

Ma Desheng, Hang Back, 2013, Acrylic on canvas, 150 x 200cm

The series of large-scale nudes executed in 2013, are painted in a range of colours in a more nuanced, mottled aesthetic, into which the huge, outlined figures are immersed, merging into the whole. These figures are contorted into various postures, in which the limbs, hands and feet are elongated and some of the poses are highly eroticised and sexualised. In Hang Back (2013) the figure is seen from behind, her large buttock and breasts dominating, her back twisted over her folded legs, hands on feet in an uncomfortable contortion of the body. In Grande Odalisque (2012), the figure is lying on her front, reaching to her feet, her legs bent backwards. In Look Back (2012), her vulva is clearly visible from behind, with a spindly hand reaching over to her thigh. In Unfold (2013), the figure’s outline is exaggeratedly formalised through curves, removing any sense of realism. The titles in this series are more assertive in tone, appearing almost as instructions, lending an uncomfortable relationship between viewer and subject, explicitly exposing the potentially violent male gaze on the female body. The exaggerated poses emphasise the physicality of the women’s bodies and their sexual power.

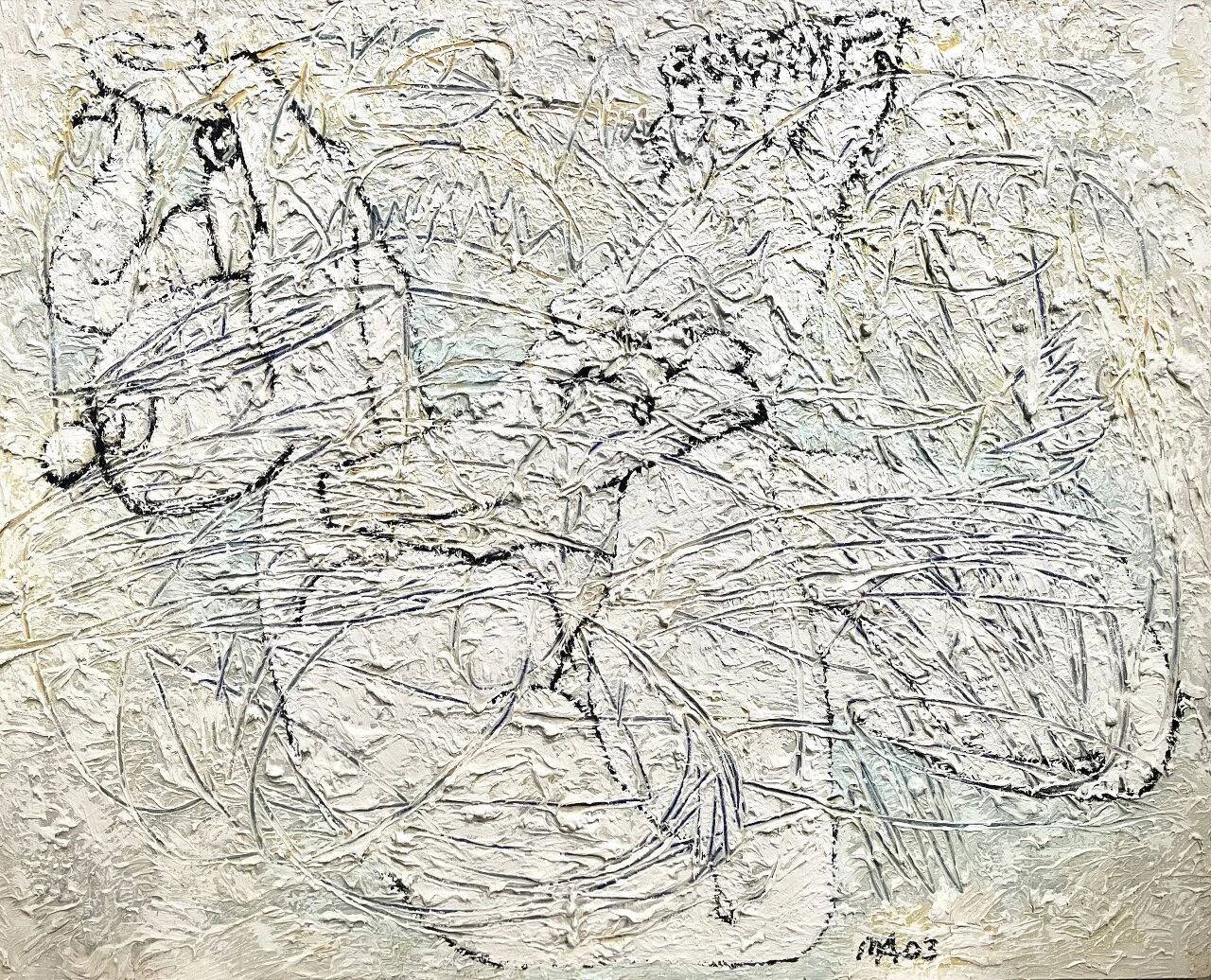

Ma Desheng, Loving Nature, 2003, Acrylic on canvas, 130 x 162cm

In Loving Nature (2003), the nude gets almost completely obliterated pictorially, fusing into an abstract blur within thickly laid paint, rendered through a strongly textured impasto technique, with lines scratched through like scribbles across the canvas. Here the painting exudes a forceful energy, frenetically expressing the title that integrates the body with the background, rendering it as one. Life and form are thereby integrated as the fundamental tenets of our world, as energy, life and earth become one, as captured in the title of the work.

These works seem, indeed are, far removed from Chinese cultural forms, signifying a global cultural turn in the 1980s due to a shift in political circumstances and a new wave of migration. In the earlier twentieth century, numerous artists from China engaged in a kind of transnational modernism and painted the female nude, developing a distinct form of Chinese visual modernity. Lin Fengmian’s (1900-1991) figures range from the cubist early works to elegant outline female nudes that are more decorative in style. Sanyu (Chang Yu, 1907-1966) painted nudes from the 1920s to the 1960s, his last nude reaching a record auction price of 198 million Hong Kong dollars in 2019. Pan Yuliang (1895-1977) stood out, as a female painter whose works included radical self-portraits and female nudes breaking the taboo of female sexuality and self-representation.

Ma Desheng, Rise and Fall, 2003, Acrylic on canvas , 114 x 648cm, polyptychs (114 x 162cm each)

Key figures in the history of Chinese art who were immersed in Parisian modernism, form the art historical backdrop to Ma’s nudes and arguably contest the narrative of modernism as a purely Western construct. Just as leading artists such as Renoir, Matisse and Gauguin were influenced by non-Western aesthetic forms that heavily informed their work, many Chinese artists in the West drew on diverse cultural sources in their subject and methodology. German expressionism, for example, has been a source of interest to leading painters such as Zeng Fanzhi. Emotionality is depicted through the body in Ma’s nudes through the elongated fingers and lively feet. Not only were the 19th century painters such as Millet highly formative in China, who was studied by Chinese art students in the academy, but leading painters such as Francis Bacon, Anslem Kiefer and Lucien Freud also strongly influenced painting in modern China.

Modernity, the nude in China

Within the Chinese context, modernity has a historical lineage dating to the collapse of the Qing (1911) and the 1920s exemplify a period of cosmopolitanism and rich cultural exchange. When Xu Beihong drew sketches of nudes, he did so to further the pursuit of realism to accurately record the body, coinciding with the emergence of a new art education system in China that brought in life-drawing and the female model, famously initiated by Liu Haisu in Shanghai. In the work of Lin Fengmian and others, their take up of the nude opposed this idea of realism, exploring how forms beyond or outside the real could bring about a global artistic language of modernity that refused a clear or prescriptive narrative.[12] From the 1930s to the 1970s, it was forbidden to be associated with modernism due to the cultural mores and narrow ideological demands of the revolution. Only decades later did the theme return, when figurative narrative painting could be replaced by modernism again. Therefore, Ma’s nudes do more than echo a Western path of modern art, they act as a decisive position in favour of what modernism stands for – cultural autonomy.

In Lynda Nead’s study of the female nude, she points out that, ‘the representation of the female body [in these images] functions as a critical sign of male sexuality and artistic avantgardism’.[13] Interestingly, male subjectivity in China has been a dominant aspect of contemporary art narratives and production until relatively recently.[14] Many older generation female artists were largely overshadowed by their male counterparts until more recently. Almost all the works from the 1990s featured male figures, often satirised in grotesque visual terms. Ma’s own (male) avant-gardism speaks to an earlier moment in cultural history, when realism was being superseded by modernism and modernism allied itself with a global visual language, neither defined by West nor East. Interestingly, his sense of powerlessness is perhaps mirrored in these vigorous female figures, who appear to be aesthetically, sensually and spiritually idolised in these works, the small phallic heads signifying a loss of male authority. Even though a gendered reading of the works might beg the obvious critique of male/female power dynamics after Laura Mulvey’s formative work on the male gaze, another reading could return to the idea of male awe and impotence in the face of female supremacy as the ultimate life-force.

Ma Desheng’s works act as a form of cultural interchange, threaded with multiple strands that make up modernity itself, as a story of cultural refraction. Yet, in an old-fashioned way, the artist has simply, in Clark’s words, ‘the wish to communicate certain ideas or states of feeling’.[15] He is a contemporary classicist in one sense, furthering his own interpretation and vision, which draws on modernism, Daoism, calligraphy and classicism. An added dimension of his oeuvre is illustrated in Ma’s visceral and eviscerating performance work La Merde (Shit), an explosive and passionate critique. In it, the artist, from his wheelchair, shouts in French ‘why, why, why is there shit?! It is everywhere, everywhere, everywhere!’, spitting out his horror at the world in a repetitive rage.[16] His strong and wonderful spirit frequently spills out beyond the canvas in his live work, allowing the audiences can experience his charisma.

These works also contain a slow, internalised energy in their rigour, variety and scale as evident by the robust and decisive brushstrokes and forms. They display a strength of hand, akin to what Clark describes as ‘so complete a fusion of the sensual and the geometric as to provide a kind of armour’.[17] Despite the continual evolution of the nude into more contemporary interpretations that now include artists exploring femininity, gender identity and queerness as discussed in a recent article, Julia Halperin also makes the point that ‘Nudes are one of the oldest and most stubbornly provocative tropes in Western art’. Here in the work of Ma Desheng, an artist situated within a globalised context of the Chinese diaspora, a crucial layer to this history is added.[18]

[1] Email correspondence with the author February 2025. ‘As for my paintings, they are all small heads, because there are so many problems in the world now because people think too much. The simpler and more natural the mind becomes, the better the world will be. You can freely express your thoughts on other questions.’

[2] Ma Desheng, in ‘Ma Desheng | La vie est nue’, Gallery Wallworks, Paris. Stephen Paradisi, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d-fAyIjSFQs.

[3] Chinese Artists in Paris (1920-1958): From Lin Fengmian to Zao Wou-Ki. An exhibition from the collections of the Musée Cernuschi, presented at the Hong Kong Museum of Art from 20 June to 21 September 2014.

https://www.parismusees.paris.fr/en/exposition/chinese-artists-in-paris-1920-1958-from-lin-fengmian-to-zao-wou-ki

[4] Huang Rui, ed. The Stars’ Times, 1977-1984, Thinking Hands, 2007. p.41.

[5] Li Xianting, in Wu Hung and Peggy Wang eds. Contemporary Chinese Art Primary Documents, p.11. Ma still uses the word ‘Freedom’ in his performances, frequently reiterating this basic tenet of human autonomy in his powerful vocal works.

[6] Huang Rui, ed. The Stars’ Times, 1977-1984, Thinking Hands, 2007. p.41.

[7] Huang Rui, ed. The Stars’ Times, 1977-1984, Thinking Hands, 2007. p.41.

[8] Huang Rui, ed. The Stars’ Times, 1977-1984, Thinking Hands, 2007. p.41.

[9] Huang Rui, ed. The Stars’ Times, 1977-1984, Thinking Hands, 2007. p.41.

[10] Sanda Miller, “Brancusi’s women”, Apollo (March 2007), 56 – 63. Quoted in Philip McCouat, ‘The Controversies of Constantin Brancusi. Princess X and the Boundaries of Art’, Journal of Art in Society, 2015. URL: https://www.artinsociety.com/the-controversies-of-constantin-brancusi-princess-x-and-the-boundaries-of-art.html

[11] Smithsonian Archives, Walt Kuhn scrapbook of press clippings documenting the Armory Show, vol. 2, 1913. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/items/detail/walt-kuhn-scrapbook-press-clippings-documenting-armory-show-vol-2-14643

[12] This positioning caught up with Lin later on in the wake of WW2 and the revolution and many of his earlier works were destroyed or lost, leaving only a partial legacy of his contribution to Chinese modernism.

[13] Smithsonian Archives, Walt Kuhn scrapbook of press clippings documenting the Armory Show, vol. 2, 1913. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/items/detail/walt-kuhn-scrapbook-press-clippings-documenting-armory-show-vol-2-14643

[14] Smithsonian Archives, Walt Kuhn scrapbook of press clippings documenting the Armory Show, vol. 2, 1913. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/items/detail/walt-kuhn-scrapbook-press-clippings-documenting-armory-show-vol-2-14643