Peter Lanyon 彼得.蘭永

Uniquely among the artists most usually associated with the St Ives school, Peter Lanyon had a particular claim on the town: in 1918, he was born there. Cornwall would remain his home for virtually his entire life; of his death in 1964, artist Nancy Wynne-Jones reflected in her later years simply that ‘He was the pulsing energy of the place’. In his abstract landscapes, Lanyon drew on a wide range of influences to create a kind of art that spoke directly to the particularities of Cornwall – its landscape, history and myths. And in the numinous quality of his paintings, one finds an engagement with the Cornish coast that is more intensely personal than that of any of his peers.

Lanyon’s work, above all, represents the confrontation of individual subjectivity with the immensity of the elements. This concern places him at the forefront of those late modernists who, in step with the existentialism of Sartre and other theorists, sought to recalibrate man’s understanding of his existence in a world still raw with the memories of war. At the same time, it positions him within a much older European tradition of landscape painting, stretching back to Romantic notions of sublime.

Both of these aspects were explored in a major Tate survey of 2010–11 which, along with a display of Lanyon’s gliding paintings at the Courtauld Gallery, London, in 2015–16, and the publication of his catalogue raisonné in 2018, have secured Lanyon’s reputation as one of the world’s most significant and original proponents of late modernism. His work is held in international collections including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Yale Center from British Art, New Haven, and other museums from Canada to Australia to Portugal.

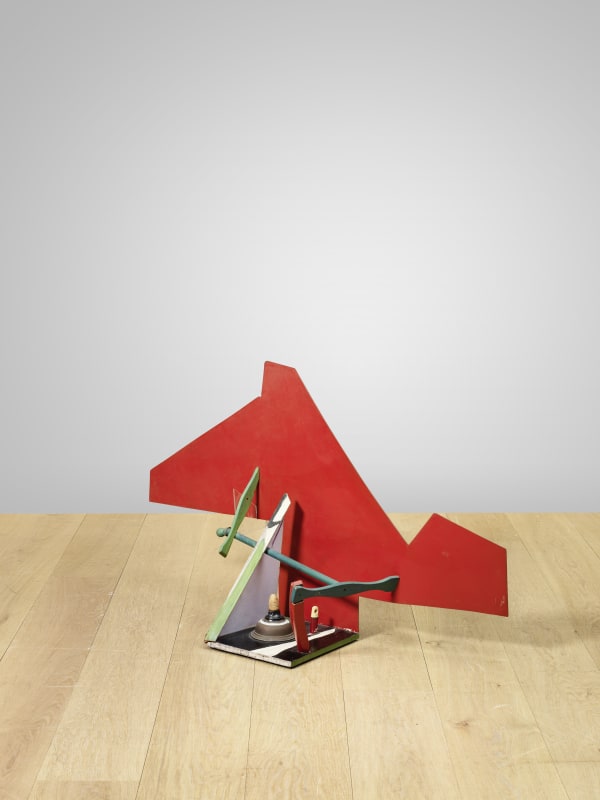

Lanyon’s first tutorials in painting with the local artist Borlase Smart involved expeditions to the Cornish cliffs, where Lanyon was encouraged to draw minutely observed images of geological formations. At the outbreak of war in 1939, the arrival of Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth and the Russian sculptor Naum Gabo in St Ives, who moved there on the advice of the critic Adrian Stokes and his wife, the painter Margaret Mellis, was a transformative moment for the young Lanyon. He later spoke of his astonishment in discovering, in Nicholson, an artist after his own heart. His work would be heavily influenced by Nicholson’s White Reliefs, as well as Gabo’s constructivist sculptures, for much of the next decade – though the late 1940s brought a falling out with Hepworth and Nicholson, as Lanyon increasingly came to believe that they had brought to St Ives an oppressive species of centralising internationalism, which threatened to level its regional peculiarities.

His art had also begun to diverge from their example. 1949 brought West Penwith, the first in a series of landscapes that captured what Patrick Heron, reviewing Lanyon’s first solo show in London that same year, described as ‘the cold grey-white light of an imaginary, almost a lunar, world’. The series would culminate in Porthleven (1951): a large-scale work, more than 2.5m high, in which Lanyon drew on long and intimate knowledge of the harbour village to create an image of mysterious, otherworldly beauty.

Lanyon learned to fly a glider in 1959 – another attempt to gain a new vantage point on the landscape he knew so well, which brought about a remarkable series of aerial sea views in the final five years of his life. It was a gliding accident that killed him in 1964, at the age of just 48 – a tragedy which has come to be thought of by many as the moment that the waves abruptly broke on the St Ives School, and began to roll back.

-

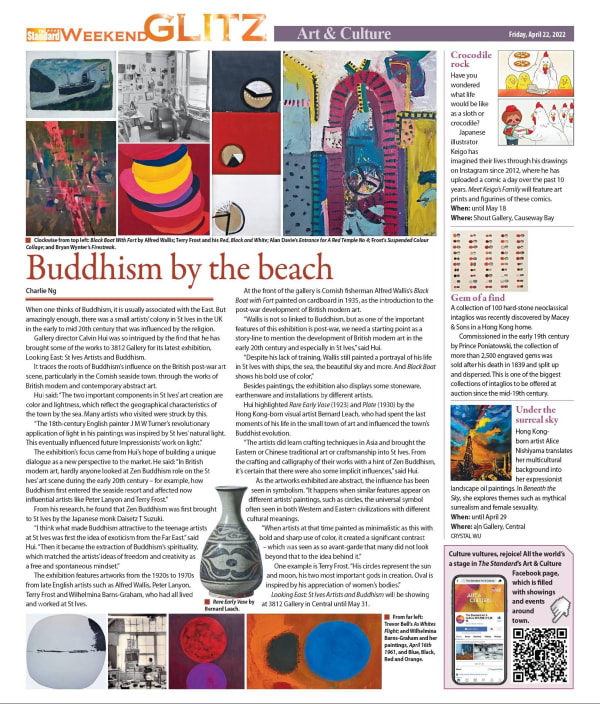

Looking East: St Ives Artists and Buddhism

13 July - 10 September 2022 LondonTouring all the way from Hong Kong to London, Looking East: St Ives Artists and Buddhism explores the unique relationship between artists working from St Ives during the post-war period...Read more -

Masterpiece London

30 June - 6 July 2022 Art Fairs, LondonFor Masterpiece London 2022, 3812 Gallery is proud to present Spirit and Landscape, a curated selection of major landscape works from the last one hundred years. One of the most...Read more -

Looking East: St Ives Artists and Buddhism

21 April - 31 May 2022 Hong KongLooking East: St Ives Artists and Buddhism explores the unique relationship between artists working from St Ives during the postwar period and Eastern spirituality. Once a small fishing village in...Read more