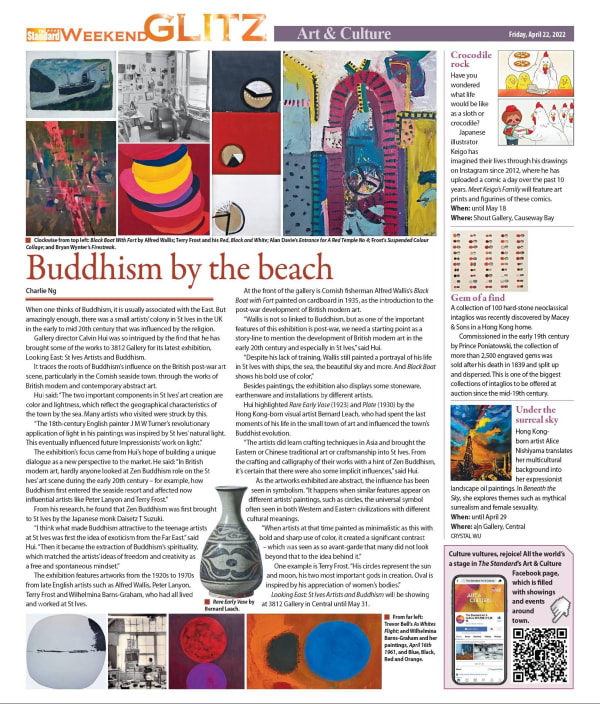

Alan Davie 艾倫.戴維

Painter, poet, jazz musician, jewellery designer and self-avowed mystic, the Scottish artist Alan Davie took a magpie’s approach to cultures both ancient and modern, plucking out ideas and symbols wherever he came across them, from realms of thought as diverse as Zen Buddhism, Hopi pottery, Pictish runes and Abstract Expressionism. His reputation proved just as far-reaching: the influential critic David Sylvester ranked him alongside Francis Bacon as the greatest living British artist, while a career spanning more than eight decades brought solo shows in public institutions from Europe to the United States, South America and Asia. A major survey was held at Tate St Ives in 2003–04; in 2014, a spotlight display opened at Tate Britain in London. Davie’s work is held in public collections across the world, including the Tate, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Seoul.

Born in 1920 in Grangemouth, Davie graduated from Edinburgh College of Art in 1941. He travelled widely after the Second World War, most significantly around Italy, in 1948, with his wife, the artist-potter Janet ‘Bili’ Gaul. There he was enraptured by the guileless beauty he perceived in Cimabue and other artists of the Italian trecento, stoking the coals of a lifelong passion for the perceived simplicity of ancient societies; he also attended the Venice Biennale of that year, encountering the work of Pollock, Rothko and de Kooning and meeting the collector Peggy Guggenheim, who bought one of his works.

After returning from Italy, Davie initially made his living by designing jewellery and playing tenor saxophone for a touring jazz outfit. For a while he painted in a loose, abstract mode heavily indebted to Pollock – but he realised that Abstract Expressionism could take him so far. His approach to abstraction soon deepened, in large part through his appreciation of improvisation in jazz, and through his reading of Eugen Herrigel's book Zen in the Art of Archery (1953), which emphasised the spontaneity prized in Zen Buddhism – ‘the intuition that knows without knowledge’. At this time, Davie worked more often than not with many paintings on the go at once – an attempt to banish premeditation from his practice, in favour of a decision-making untainted by rationalism.

From the late 1950s he began to incorporate, alongside his own invented forms, symbols from a host of ancient cultures, ranging from Aboriginal rock-carvings to Native American pottery. His New York solo show in 1956 proved a sell-out, with paintings bought by institutions including MoMA; acclaim in Britain came two years later, with a retrospective that opened in Wakefield and travelled to the Whitechapel in London, putting him firmly at the forefront of the British avant-garde.

Davie was appreciated early in St Ives. In an essay of 1955, Patrick Heron praised his paintings for possessing ‘the poetry of pigment, the phantasy of paint itself’. It was friendship with Heron, above all, that lured Davie to the south coast in the late 1950s, where he set up a studio near Land’s End. In 1960, Davie paid tribute to his friend with Patrick’s Delight – a vivid oil painting in triptych format, bearing echoes of Heron’s stripe paintings and marking a definitive move away from the earlier Ab-Ex-inspired paintings toward a tighter, more controlled form of mark-making. Davie always thought of it as one of his most important works. It was named for the raptures into which it had sent Heron when he saw it hanging up in Davie’s studio – an improvised title, conjured on a whim, which in many ways sums up Davie’s approach both to life and to art-making.

-

Looking East: St Ives Artists and Buddhism

13 July - 10 September 2022 LondonTouring all the way from Hong Kong to London, Looking East: St Ives Artists and Buddhism explores the unique relationship between artists working from St Ives during the post-war period...Read more -

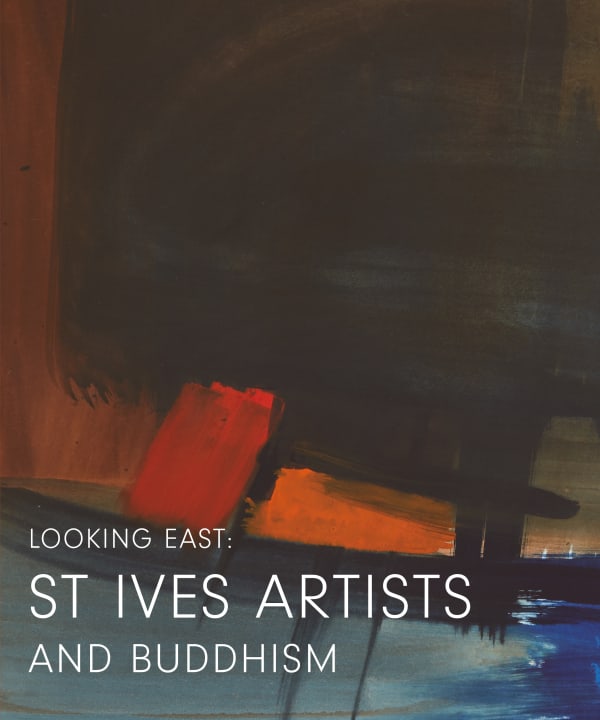

Looking East: St Ives Artists and Buddhism

21 April - 31 May 2022 Hong KongLooking East: St Ives Artists and Buddhism explores the unique relationship between artists working from St Ives during the postwar period and Eastern spirituality. Once a small fishing village in...Read more